f.a.n.

“Funding for the Arts Network” is a collective of researchers, scholars and practitioners interested in exploring the new (and the old) funding and financing models for the arts and culture. We are by nature interdisciplinary.

23rd ACEI Conference 2025

in Rotterdam

—

Post written by Aline Albertelli

Rethinking Cultural Financing: Alternative Models and the Future of Sustainable Cultural and Creative Practices

At the 23rd ACEI Conference in Rotterdam, scholars and practitioners gathered to exchange ideas across a wide spectrum of topics within cultural economics. While the program addressed everything from labor markets in the creative industries to digital and green transitions and cultural policy evaluation, one area stood out for its urgency and cross-cutting relevance: the future of financing and funding in the cultural and creative sectors.

A dedicated session, Funding and Financing for Arts and Culture: Novel Perspectives, moderated by Carolina Dalla Chiesa, Ellen Loots, and Anders Rykkja, brought together a range of contributions exploring theoretical and empirical perspectives on access to funding, remuneration, and financing opportunities. These discussions are increasingly vital in an era marked by shifting political priorities, rapid technological innovation, and evolving social expectations. The session showcased emerging models of alternative financing, new forms of participation, and the evolving role of technological tools and governance frameworks in shaping access to cultural resources.

The papers presented in the session challenged conventional boundaries of cultural finance. Aline Albertelli and Anna Mignosa examined the influence of public-private partnerships (PPPs) across different governance contexts. Their analysis underscored the critical role of well-designed policy and governance frameworks, especially in countries with centralized modes of governance —not merely to provide funding, but to create enabling environments where cultural initiatives can thrive independently over time. Lluis Bonet added to the governance discourse drawing attention to the enduring tension between efficiency and legitimacy in public funding. He presented a comparative perspective on direct government expenditure in the cultural sector and the way in which money is spent depending on the state's governmental structure.His work emphasized that debates over cultural budgets are never just technical; they reflect deeper institutional choices. He also highlighted a long-standing and pressing need for more — and especially clearer and more precise — data on how funds are used and devolved, something that remains lacking at the European level.

A recurring theme throughout the session was the reconfiguration of relationships between funders, creators, and audiences in the context of accelerating digital technologies. Alice Demattos Guimarães and Natalia Mæhle explored crowdfunding not only as a financial mechanism but also as a participatory, relational process. In this model, backers become active stakeholders in the creative journey in which the traditional boundaries between producer and audience start to blur. Elisabetta Lazzaro similarly investigated digital tools and funding models in the heritage sector, where museums and cultural institutions are exploring online engagement, decentralized financial platforms, and onsite digital tools. Both studies shed light on how digital infrastructures can support innovative funding practices in ways that navigate the tensions between artistic autonomy, cultural value, entrepreneurship, and technological transformation.

Joost Heinsius, together with Isabelle De Voldere, introduced the concept of impact investing in the cultural sector. Their presentation explored how frameworks typically applied to social enterprises or environmental initiatives are being adapted to fund cultural projects. While rich with potential, integrating impact metrics into cultural finance also raises important questions about evaluation, comparability, and how cultural value and “impact” are defined and measured.

Taken together, these presentations illustrated that alternative funding and financing mechanisms are not simply technical innovations, but part of a wider transformation in how culture is valued, governed, and sustained. Whether through co-creation, digital participation, or cross-sector partnerships, these emerging models are reshaping not only the financial sustainability of the cultural sector but also the social contracts that underpin it.

To extend the conversation beyond the conference, several contributors joined the newly established Funding for the Arts Network (FAN)—initiated by Carolina Dalla Chiesa, Ellen Loots, and Anders Rykkja. FAN aims to bring together scholars, policymakers, funders, and practitioners to explore innovative, inclusive, and resilient approaches to cultural finance. The network seeks to foster interdisciplinary dialogue and co-develop new frameworks for thinking about remuneration, funding, and financing in the arts.

In the face of global cultural policy shifts, economic uncertainty, and technological disruption, the ACEI 2025 session on alternative financing made it clear that renewed attention is needed to the structures—both traditional and emerging—that allow culture to flourish. The discussion is far from over. But what emerged in Rotterdam was clear: the future of cultural finance will depend on cross-disciplinary and cross-sector collaboration, thoughtful strategies, shared values and dictionaries, and a willingness to embrace the unfamiliar, the experimental, and the untried.

Full list of contributions:

● New and Traditional Forms of Funding the Arts and Creative Sectors: The Role of Public-Private Partnerships (Aline Albertelli, Anna Mignosa)

● Efficiency vs. Legitimacy: Rethinking Direct Government Expenditure in Cultural Policy (Lluis Bonet)

● (Co-)Creating Digitally: The Relational Art of Funding Cultural Projects through Crowdfunding Practices (Alice Demattos Guimarães, Natalia Mæhle)

● Exploring Impact Investing in the Cultural and Creative Sectors: Opportunities, Challenges, and Emerging Models (Joost Heinsius, Isabelle De Voldere)

● Current and Prospective Digital Funding and Financing in Cultural Heritage (Elisabetta Lazzaro)

ACEI 2025 took place from 25 to 27 June 2025 at the Erasmus University Rotterdam. The present text intends to highlight the main takeaways from a proposed session (Funding and Financing for Arts and Culture) on 26 June, 8.30am.

First FAN meeting at the ACEI 2025.

From left to right: Anna Mignosa, Lluis Bonet, Ellen Loots, Jooost Hensius, Alice Demattos, Elisabetta Lazzaro, Aline Albertelli, Anders Rykkja, Carolina Dalla Chiesa.

Funding Culture or Funding Control?

The Trade-Offs Dutch Museums Can’t Escape

—

Post written by Fabiana Basili

Museums walk on a fine line. They are driven by their mission to inspire, educate, and preserve heritage, but staying financially sustainable is a constant challenge. Structural issues in the cultural sector, well known in cultural economics, have become even more pressing after the pandemic and fears of budget cuts in the Netherlands (Cultuurmonitor, n.d.a, b; Museumvereniging, 2024; Education and Sports Ministry outlines major grant cuts, 2024). Granted, this isn't exactly a groundbreaking discovery… But why does it persist so stubbornly? Here’s a closer look at the internal strategic reasoning and external pressures that continue to shape this reality.

This article summarizes the findings of a Master’s thesis in Cultural Economics and Entrepreneurship, exploring how Dutch museums pursue financial health while staying true to their broader organizational goals. Focusing on four case studies—the Wereldmuseum in Rotterdam, Groninger Museum, Catharijneconvent in Utrecht, and Zeeuws Museum in Middelburg—it examines how they manage funding dependency, particularly on government support. The research uses a mixed-methods approach, combining analysis of financial statements (2021–2024) and interviews conducted with museum managers.

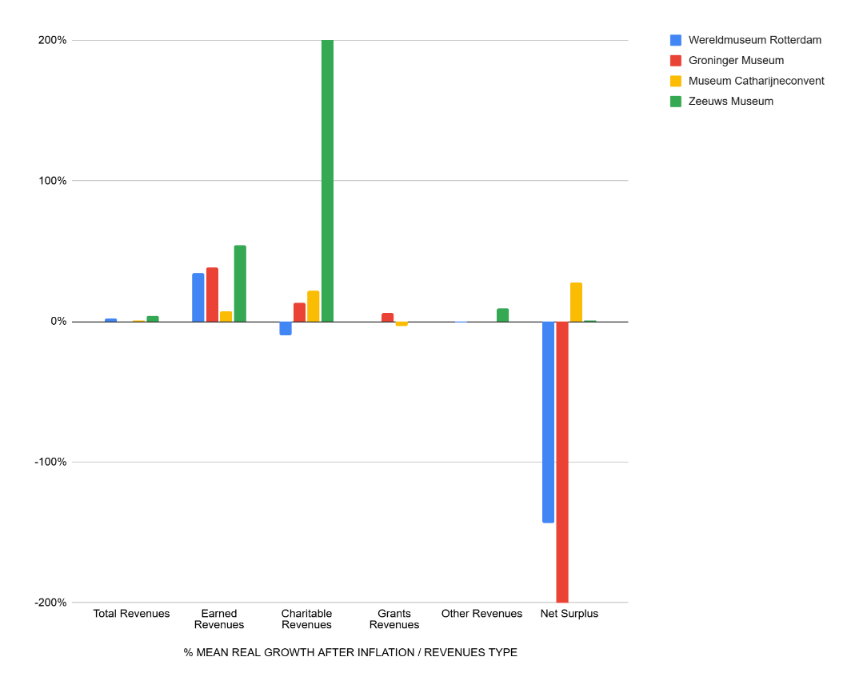

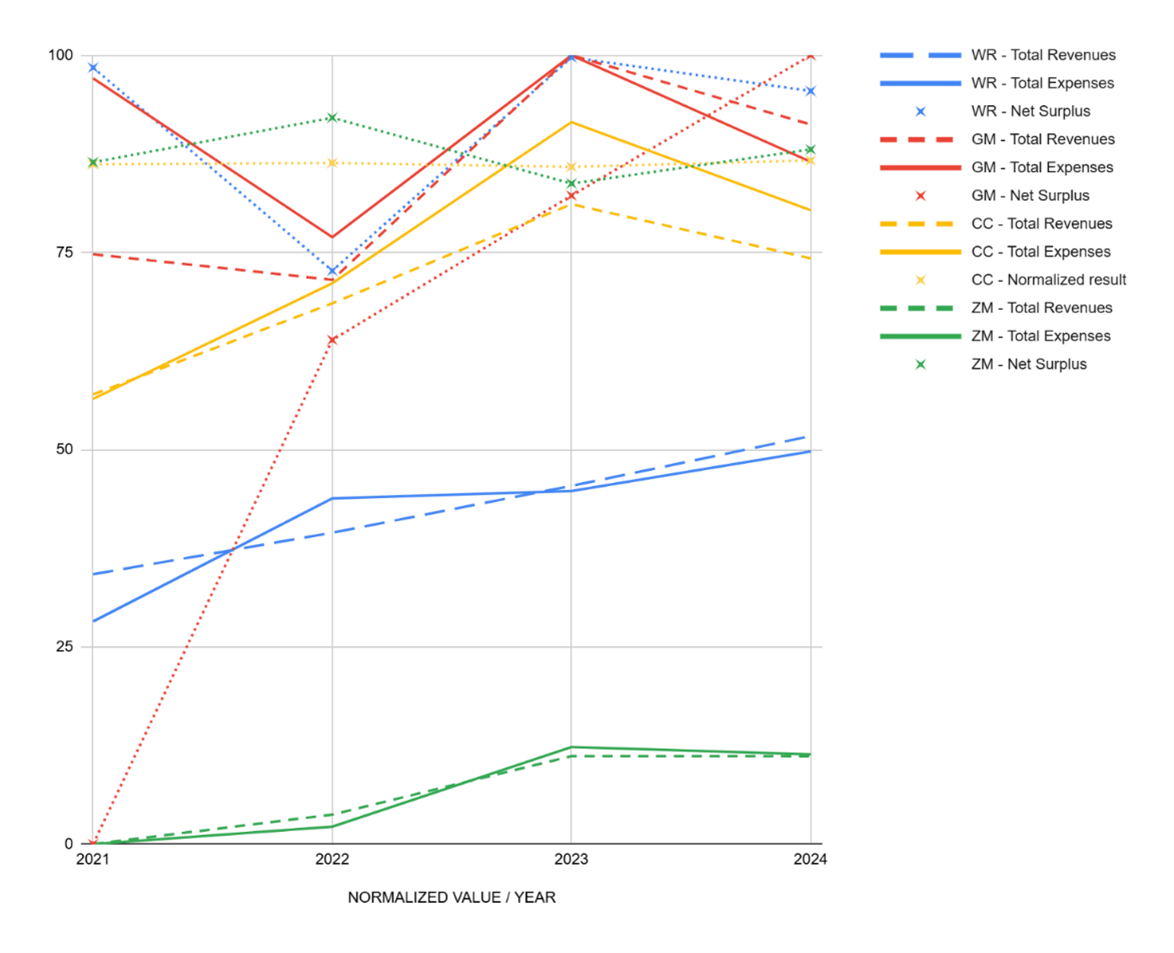

We begin with an overview of the case studies, which reflect national trends: between 2021 and 2024, both revenues and expenses rose (Figures 1 and 2) While this was partly due to the low post-pandemic baseline in 2021, broader economic pressures, including an increase in the inflation rate, also played a role. However, in most cases, expenses increased faster than revenues, posing challenges for financial stability. Government funding has increased, but it still struggles to keep pace with these changes. This pattern aligns with national data, though the four case study museums performed slightly better. Generally, medium-to-large institutions showed greater adaptability yet still faced negative results in recent years (Museumvereniging, 2022, 2023, 2024; Verwey, 2025).

Figure 1.

Mean real growth of revenues and net surplus adjusted to inflation

Note. The Zeeuws museum’s charitable revenues (+1,128%) and the Groninger museum’s net surplus (-247%) show exceptionally high values, exceeding the visual limits of the current chart scale.

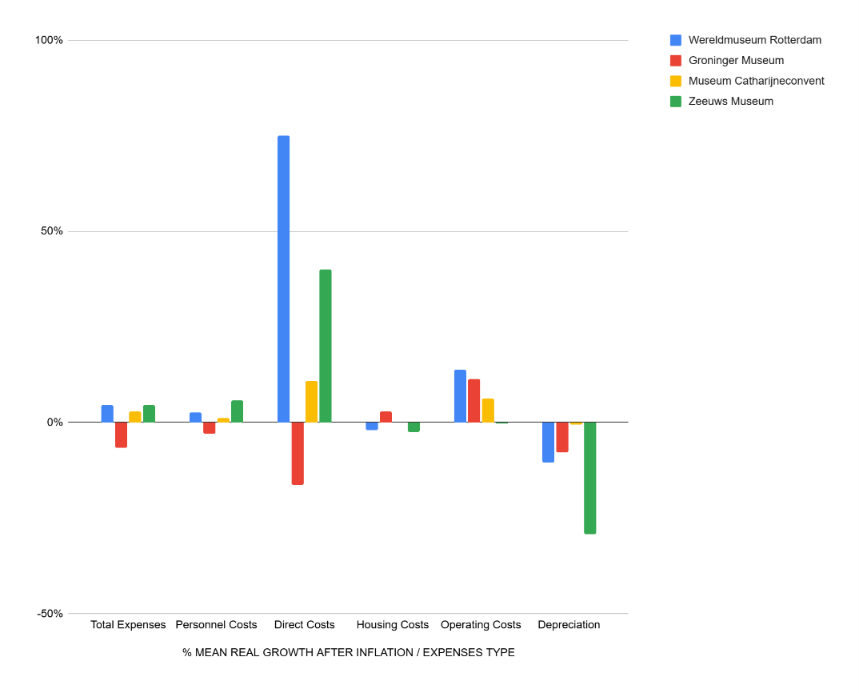

Figure 2.

Mean real growth of expenses adjusted to inflation

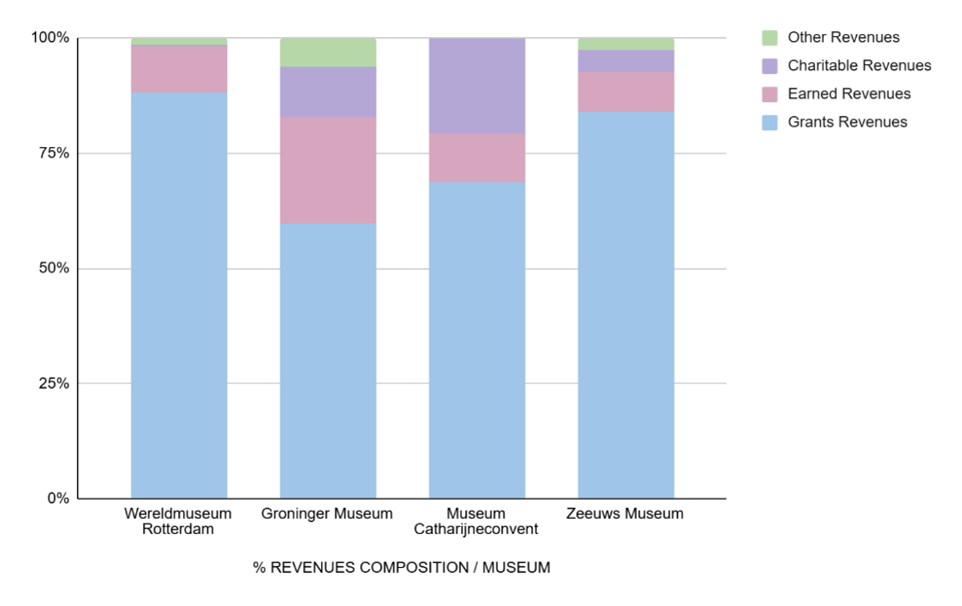

To understand the financial health of museums, it's essential to start by acknowledging their condition of resource dependency. The four Dutch case studies reveal a strong reliance on government funding to sustain infrastructure and core programming. Alongside charitable contributions, these resources are often beyond their direct control. Other revenue streams remain limited and typically support additional activities. Efforts to boost self-generated income are limited by the nature of cultural offerings as public goods: museums struggle to "marketize" these goods without either excluding part of the public or shifting away from their core values (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Mean distribution of the source of revenue by percentage

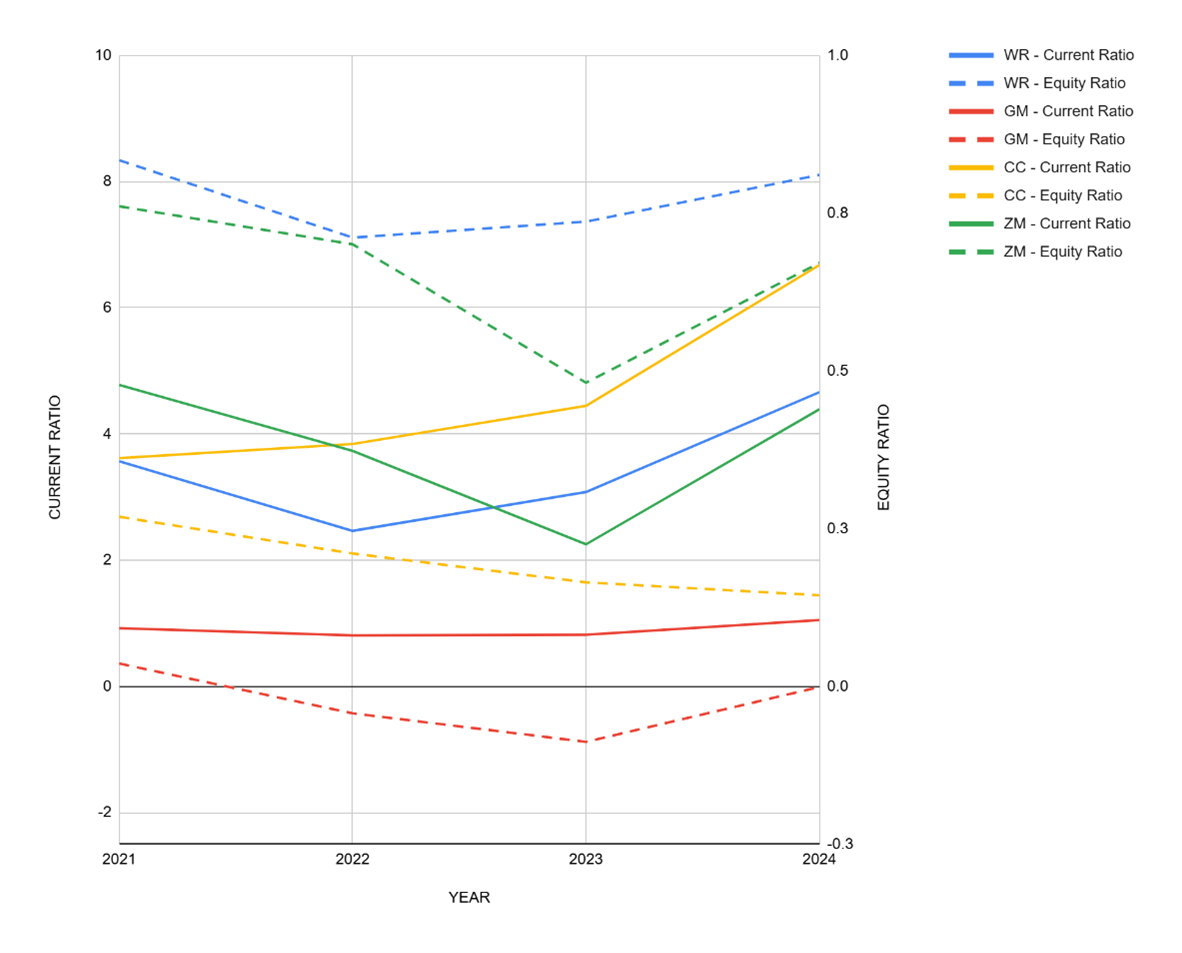

Financial health can be understood in terms of economic capacity and sustainability. The four Dutch museums generally show strong financial capacity, meaning they can meet both current and future spending needs, largely thanks to stable government support. In two of the four case studies, the situation is slightly more fragile, but still under control and actively managed through strategic planning (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Financial capacity: Liquidity and solvency trends across museums

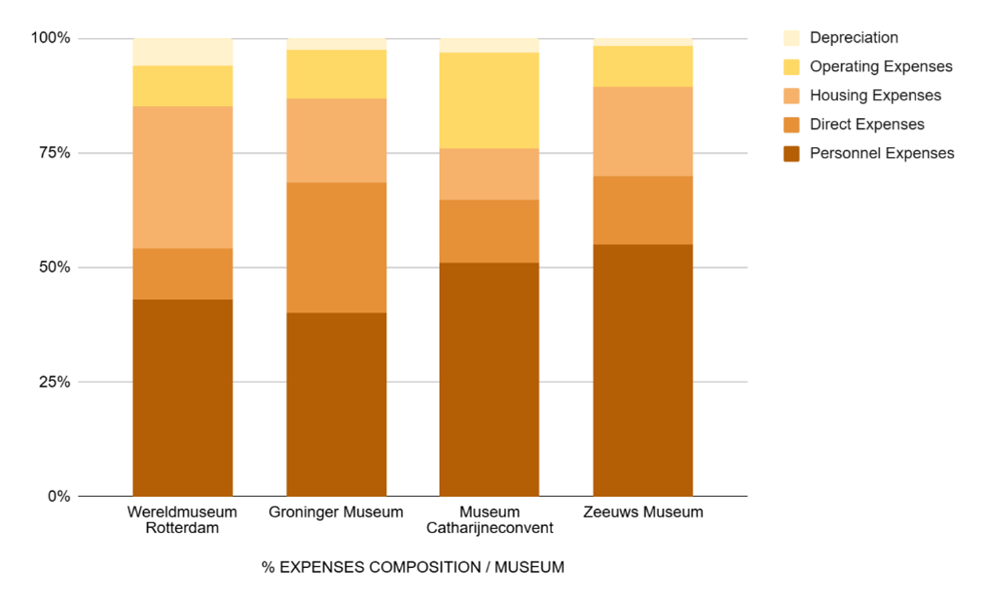

When government support is not guaranteed, financial capacity is at risk, as developing revenue is challenging as much as cost control. Like many cultural institutions, museums face high fixed costs, with high personnel and core programming expenses (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Mena distribution of the type of expenses by percentage

Under financial pressure, these are often the only flexible areas to adjust, leading to a more precarious job market and a reduction in core activities. This is confirmed by the fact that the museum’s size appears to be related to the amount of government contribution, suggesting that when the government is the main revenue source, smaller investments result in smaller cultural organizations (Figure 6). As museum managers also stated, less public funding means fewer core cultural offerings. That said, the sector faces uncertainty about future solutions development, it often feels stuck, as if no alternatives exist, and this challenge remains largely unaddressed.

Figure 6

Log-normalized development of revenues, expenses, and net surplus among the museums

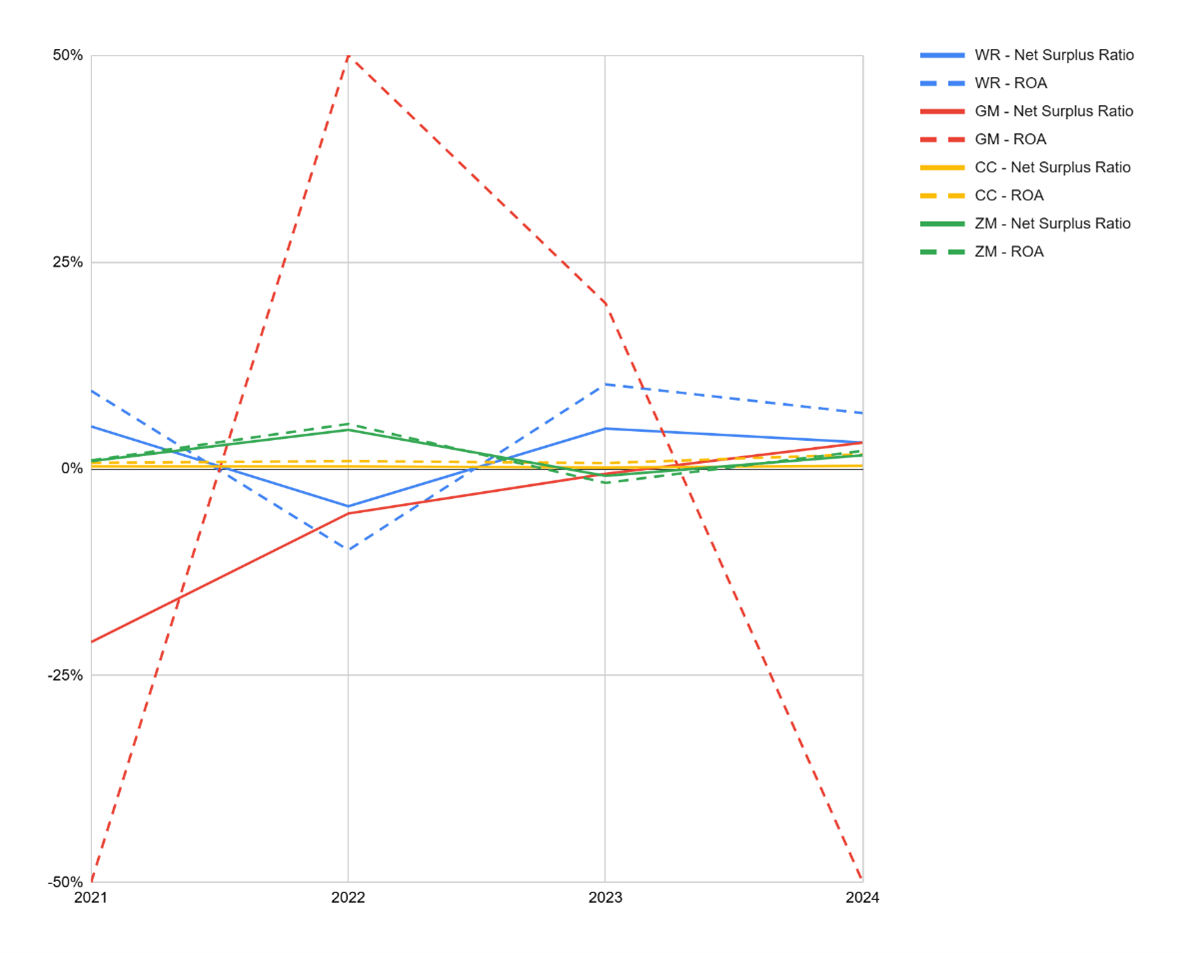

When it comes to financial sustainability, challenges emerge more strongly. Museums struggle to plan for future growth or cushion potential downturns. In other words, while day-to-day operations are well-covered, building financial resilience for the future remains an open issue (Figure 7). This is found to be linked to limited net surplus and reserve accumulation opportunities.

Figure 7

Financial sustainability: Margin and profitability trends across museums

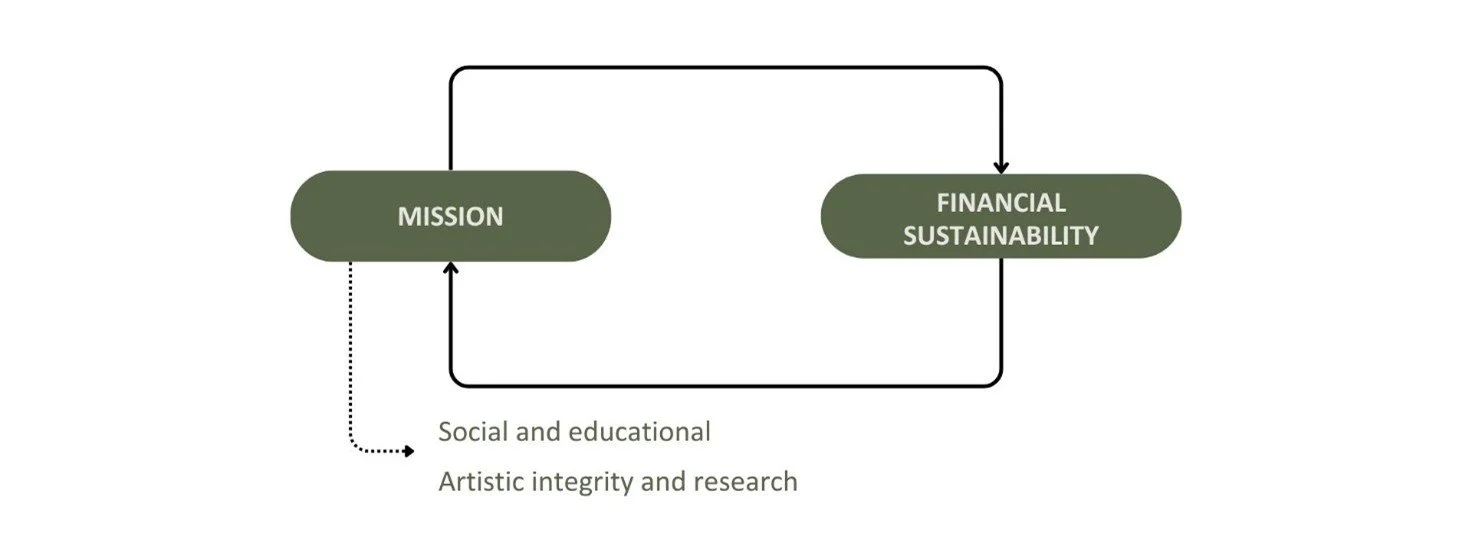

Note. The Groninger museum shows exceptionally low ROA values (up to -5,808% in 2024, mean - 1,632%), exceeding the visual limits of the current chart scale. Limited net surplus has several causes. First, relying on stable public funding allows museums to prioritize their social and educational mission. Financial choices aim at financial sustainability rather than net surplus generation, with strategic goals shaping decisions in a back-and-forth process between impact and resources (Figure 8). In this context, government dependency enables the production of public cultural goods, but it also reinforces museums' dependent status, limiting financial autonomy.

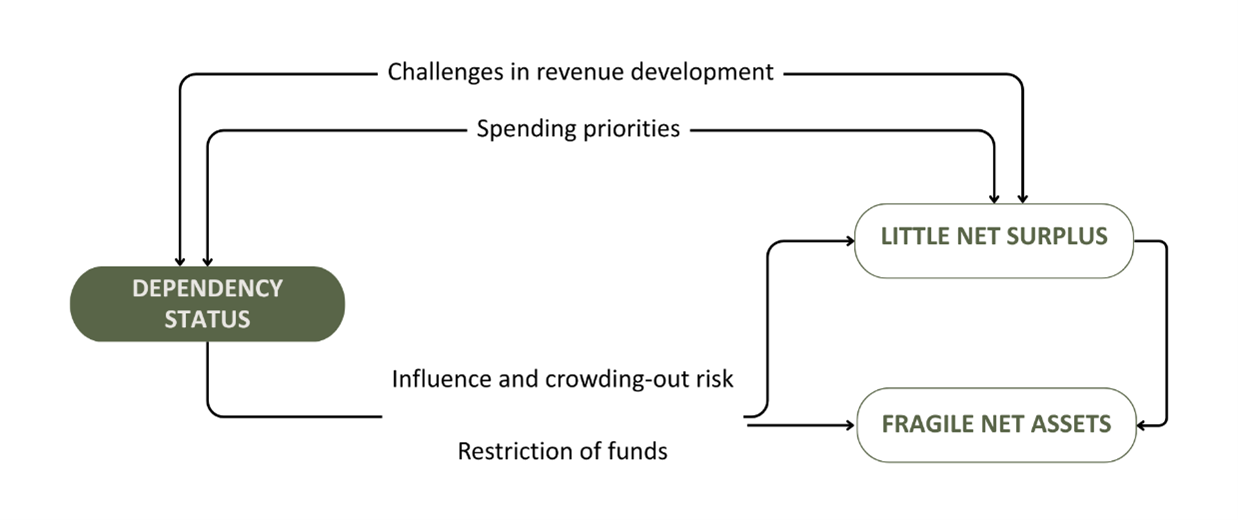

Figure 8

Relationship between principles of decision-making in the case studies

Second, museums’ resource development remains limited due to several challenges that reinforce their dependency. These include limited funding opportunities, high competition, scarce internal fundraising capacity, and uncertain outcomes from development efforts. Third, some funds are restricted to specific uses: they must be returned if unspent, meaning museums strategically aim to make the best use of what they receive, without the possibility of generating a high net surplus or accumulating reserves. Finally, crowding-out effects from public funders are also relevant, as high surpluses may lead museums to be perceived as no longer in need of future support. Concerning reserve accumulation, it remains challenging due to slim surplus margins, restricted funds, and the risk of reduced support when reserves appear sufficient. These dynamics are represented in the following framework (Figure 9).

Figure 9

Limited net surplus and reserves in relation to resource dependence status

This reveals how museums pursue financial sustainability: they often rely on a combination of cautious reserve-building, ongoing dialogue with public institutions, and targeted efforts to expand income through project-based or special funding. However, these strategies are time- and resource-intensive and often yield uncertain results. As a result, growth is a slow and incremental process.

In this context, dependency on government funding both enables and constrains museums’ financial structure, highlighting a clear trade-off. When public support is stable, museums can prioritize social impact and long-term sustainability over profit. This reinforces their financial dependency, ensuring financial capacity in the short term, but leaving long-term sustainability reliant on future policy decisions. Given structural challenges in developing alternative resources, museums remain vulnerable when it comes to growth and resilience during financial downturns. Conversely, less government intervention pushes museums to adopt a more market-oriented and entrepreneurial approach, with the risk of weakening their public social impact and shifting towards entertainment-driven content. Financial capacity and sustainability are more in the hands of management, only if the policy allows flexibility for it, though. Policy plays a crucial role in shaping this balance. When public funding is stable and guaranteed, stricter conditions may be justified, as the financial vulnerability caused by dependency is covered under the shadow of government support. However, if stability is lacking, excessive restrictions on fund use and crowding-out dynamics can hinder museums’ ability to build financial independence and resilience. Without aligning policy with the actual level of government support, museums may face significant barriers to achieving financial health.

The core issue is that resources are always stretched too thin to cover every need. Government dependency and consequent funding control are beneficial for society and museums, and their management benefits from stability. In a period where policy seems to be shifting toward reducing public intervention, it is essential that this does not simply mean cutting funds. Instead, it should involve rethinking resource distribution criteria and offering museums real opportunities for alternative revenue generation. The analysis highlights that one of the greatest challenges for museums is the difficulty of developing alternative funding sources as their mission and cultural content are often inflexible and not easily “monetized." It appears that both policy and museum management need to work toward developing a funding culture that takes these dynamics into account. This leads to two key questions for the future: How can policy support its goals of reducing direct intervention and simultaneously support the rise of alternative funding opportunities for these institutions? How can museums develop more autonomous financial models while balancing internal priorities with the external pressures of a shifting political and economic environment? True, no one has cracked the code yet, but if turning financial survival into an art form is possible, museums are well equipped to lead the way.

REFERENCES

Cultuurmonitor. (n.d.a). Jaarrapportage. [Annual report]. Retrieved April 9, 2025, from

https://www.cultuurmonitor.nl/en/jaarrapportage/.

Cultuurmonitor. (n.d.b). Beeldende Kunst. [Visual Arts]. Retrieved April 9, 2025, from

https://www.cultuurmonitor.nl/en/domein/beeldende-kunst/.

Education and sports ministry outlines major grant cuts. (2024, October 24) Dutch News.

https://www.dutchnews.nl/2024/10/education-and-sports-ministry-outlines-major-grant-

cuts/.

Museumvereniging. (2022, September). Museumcijfers 2021. Trend in the museum

sector. Retrieved 07/06/2025 from: https://museumvereniging.nl/wp-

content/uploads/2023/10/2021-Museumcijfers.pdf.

Museumvereniging. (2023, October). Museumcijfers 2022. Trend in the museum

sector. Retrieved June 7, 2025, from https://museumvereniging.nl/wp-

content/uploads/2023/10/2022_Museumcijfers.pdf.

Museumvereniging. (2024, September). Museumcijfers 2023. Trend in the museum

sector. Retrieved June 7, 2025, from https://museumvereniging.nl/wp-

content/uploads/2024/09/Museumcijfers-2023-.pdf.

Verwey, J. (2025, April 15). Jaarverslag 2024. [Annual report 2024]. Cultuurmonitor.nl.

Retrieved on June 7, 2025, from https://www.cultuurmonitor.nl/en/domein/erfgoed/.

Book publication